It is almost unimaginable today that the skies above this aspirational new community were, for nearly three decades, the battlements of Britain’s fighter fortress. But nearly 80 years ago there was a different sort of community built where Kings Hill now stands: RAF West Malling – a place of fighter planes and defiant courage in the face of sudden death – A place of landings.

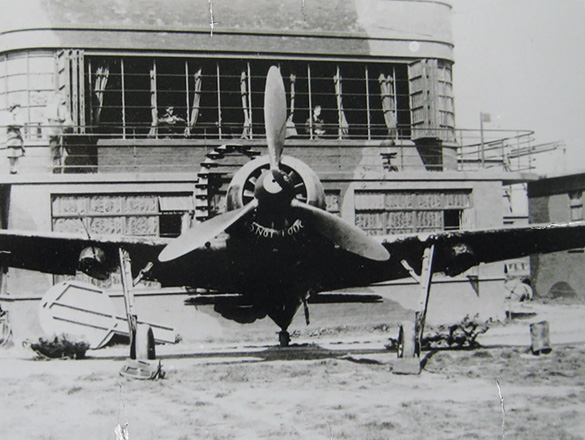

A captured Focke-Wulf 190 awaits evaluation outside the Control Tower in 1943.

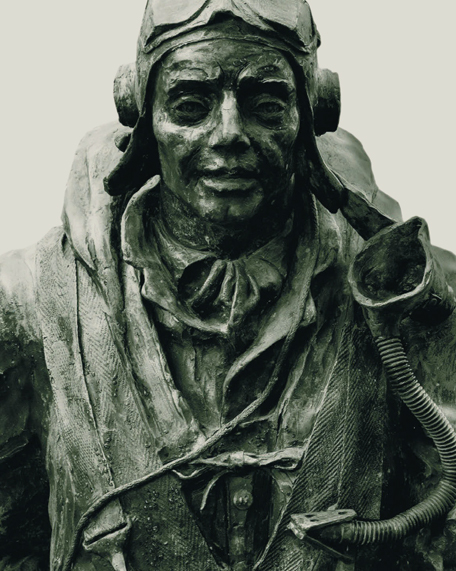

A Place of Landings, a series of artworks by artist Richard Wolfstrome.

From its earliest beginnings, RAF West Malling was both the front line and the last line of Britain’s’ defences during World War II and beyond. Above the fields now full of homes, schools and commerce, the future of the world was being measured out in the skill of young pilots and their flying machines.

Anyone venturing into the apple orchards surrounding the base during the conflict would have discovered a very strange fruit indeed. With Luftwaffe bombers relentlessly pounding the base, its squadron of de Havilland Mosquitoes had to be hidden. So special tracks were laid so the vital planes could be wheeled out of sight, hidden under the leafy safety of the boughs of the fruit trees.

It was a world and a time where life and death turned on a sixpence. The men of RAF West Malling flew fast, played hard, and, tragically, frequently died early. Spitfires, Hurricanes. Bristol Beaufighters, Defiants criss-crossed the skies by day and night. The base became famous for its night fighters and the daylight skills of its Spitfire pilots who developed a technique for speed matching and flipping the much feared V1 doodlebug flying bombs, destroying them before they could reach their defenceless targets.

When Group Captain Peter Townsend arrived as Station Commander in 1943, he was already a hero of the Battle of Britain. A dashing Hurricane pilot with film star good looks, his charisma and charm would later capture the heart of Princess Margaret.

This was, though, only the base’s first close encounter with royalty. The second came in the 1950s when one of the Vampire jet fighter crews from 25 Squadron reported a blinding light moving faster than any aircraft could. Within weeks, an aide to the Duke of Edinburgh – a keen ufologist – was in touch on HRH’s behalf, asking to look at the reports of the mysterious sighting.

When strays from a flight of German Focke-Wulf 190 fighter bombers got lost on their way back to occupied France, they mistook RAF West Malling for their home base and began to land. One – piloted by Otto Bechtold – made a perfect touchdown and then taxied calmly up to the Watch Office. A picture of his plane now covers an entire wall inside the restored building.

A second pilot – Fritz Setzer – realised his mistake and tried to take off again. His plane was shot to pieces by an armoured car and wounded Setzer fled on foot, uniform ablaze because of leaks from his severed fuel lines. He was rugby tackled to the ground by Townsend, smothering the flames.

By now it seemed the Wing Commander might have had enough of the Luftwaffe using his runway and he turned off all the landing lights. A third Focke-Wulf 190 crash-landed safely nearby. A fourth didn’t, and crashed, killing its pilot.

The Focke-Wulfs – technically superior to anything the RAF had in the air – were spirited away for exhaustive assessment by RAF engineers. In 1997, Setzer – who had remained close to Townsend – was found after the war and he returned to Kings Hill as a guest of honour at the opening of a housing development. He explained: “If anyone had told me 53 years ago that I would be invited back here by the British, I should have told them they were mad.”

In 1997, Setzer – who had remained close to Townsend – was found after the war and he returned to Kings Hill as a guest of honour at the opening of a housing development.